By Saabira Chaudhuri

ÉVIAN-LES-BAINS, France -- Bottled water, which recently

dethroned soda as America's most popular beverage, is facing a

crisis.

A consumer backlash against disposable plastic plus new

government mandates and bans in places such as zoos and department

stores have the world's biggest bottled-water makers scrambling to

find alternatives.

Evian this year pledged to make all its plastic bottles entirely

from recycled plastic by 2025, up from 30% today and among the

boldest goals in the industry. Executives at parent company Danone

SA hope the move will help it regain market share and win over

plastic detractors who are already pressuring the makers of straws,

bags and coffee cups.

There's a big problem. The industry has tried and failed for

years to make a better bottle.

Existing recycling technology needs clean, clear plastic to make

new water bottles, and bottled-water companies say low recycling

rates and a lack of infrastructure have stymied supply. Danone, for

its part, is betting the reputation of its flagship water brand on

a new technology that claims to turn old plastic from things like

dirty carpets and sticky ketchup bottles into plastic suitable for

new water bottles.

"People are really concerned about what's happening with the

packaging," said Igor Chauvelot, who works on sustainability issues

for Danone. "It's a concern and an opportunity at the same

time."

Bottled-water sales have boomed in recent decades amid safety

fears about tap water and a shift away from sugary drinks. Between

1994 and 2017, U.S. consumption soared 284% to nearly 42 gallons a

year per person, according to Beverage Marketing Corp., a

consulting firm.

That growth has been driven by single-serve bottles, which now

make up 67% of U.S. sales. Until the early 2000s, water was mainly

sold in big jugs for homes and office coolers. More recently,

images of bottles overflowing landfills and threatening sea life

have soured consumers. Plastic drink bottles are the third most

common type of item found washed up on shorelines -- behind

cigarette butts and food wrappers -- according to the Ocean

Conservancy, a nonprofit.

Bottled-water volume growth is forecast to slow this year in

both the U.S. and globally, according to research firm Euromonitor.

Nestlé SA, the world's biggest bottled-water maker, in October said

its bottled-water volumes for the first nine months of the year

declined 0.2%, compared with 2.1% growth a year earlier.

Maura Riggs kicked her bottled-water habit in April after seeing

a deluge of news stories and photographs on Twitter about how

plastic waste is hurting ocean life. "I told my husband that I

don't want to do this anymore," said the 37-year-old budget

analyst, who for a decade had lugged home 120 bottles every

month.

The Indianapolis-based couple fill 16-ounce reusable tumblers

with filtered tap water to drink at home and in the car. "It's

cumbersome, maybe a bit, but it's totally worth it," said Ms.

Riggs.

Offices, department stores, zoos and other public spaces on both

sides of the Atlantic have stopped selling bottled water. A string

of towns in Massachusetts have banned the sale of small bottles. A

proposed bill in New York City would outlaw the sale of single use

plastic bottles in city parks, golf courses and beaches.

The European Parliament in October backed laws to make member

states collect 90% of plastic bottles for recycling by 2025. Cities

including London and Berlin have encouraged local shops and cafes

to display stickers saying they will fill reusable water bottles

free. Mumbai this year banned water being sold in small

bottles.

Companies are searching for answers. PepsiCo Inc. in August

agreed to buy SodaStream -- a maker of countertop machines that

carbonate tap water -- saying the $3.2 billion deal would help it

go "beyond the bottle." Pepsi also now sells reusable water bottles

that come with capsules to add flavors, and is testing stations in

the U.S. that dispense Aquafina-branded water in different

flavors.

Poland Spring-owner Nestlé is rolling out glass and aluminum

packaging for some brands and researching ways to make all its

packaging recyclable or reusable by 2025.

"The importance of this now has sunk in," said Beverage

Marketing Corp.'s Chairman Michael Bellas, who has followed the

drinks industry for the past 46 years. "It's the total broadened

awareness of the environment, especially with millennials."

Still, executives aren't looking to get rid of plastic, which is

cheap, robust and lightweight. A former Nestlé executive said the

company's internal research showed consumers were unlikely to take

to boxed water. Glass bottles, meanwhile, break easily and are

expensive to transport because they are heavy.

"It's tempting to romanticize a world without packaging,"

Coca-Cola Co. CEO James Quincey wrote in a blog post this year.

"Modern food and beverage containers help reduce food spoilage and

waste. They limit the spread of disease."

For the bottled-water industry, the challenge has been to find a

recycled product that meets regulatory standards for food-grade PET

plastic, which is used in bottles. So far, the industry has relied

on a recycling method that washes, chops and melts waste plastic to

create resin. Most of it gets turned into clothes and carpets since

plastic loses some of its structural properties and becomes

discolored with each recycle, diminishing the appeal to

bottled-water makers.

Cedric Dever, at the time an Evian packaging manager, learned in

2016 of a new process that claimed to turn a variety of waste

plastics into clean, high-quality material. "It seemed to be so

magical," said Mr. Dever, adding he wondered if it was "too good to

be true."

A Montreal-based startup, Loop Industries Inc., had developed a

process to break plastic into its base ingredients. The process

didn't use heat or pressure, so contaminants didn't melt into the

plastic and could be filtered out. Daniel Solomita, Loop's CEO,

likened it to disassembling a chocolate cake into its ingredients

-- sugar, flour, chocolate, eggs and butter -- to make a brand new

cake.

He said other technologies, in contrast to Loop's, are limited

because they can process far fewer materials into new,

bottle-quality plastic. "They're all fighting for that clean, clear

plastic bottle because that's the only type of feedstock they can

use," he said. "We don't have supply constraints."

Mr. Solomita said he first began searching for ways to make

waste plastic usable after leading a project to remove 40 million

pounds of nylon fiber mixed with dirt from a landfill.

Mr. Dever and Danone executives had the process tested at Loop's

pilot plant -- bringing their own waste plastic secretly tagged

with a tracer to make sure that the returned samples were of the

same material.

They had the tests repeated with different types of waste,

including carpet fibers and colored plastic. "We tried to stretch

to the max the Loop technology by giving them materials we couldn't

use," said Frederic Jouin, R&D packaging head for Danone

Waters.

The resulting samples, once turned into bottles in France, met

Danone's quality standards.

Loop has yet to scale up its technology, and the company said

its production plant won't be ready until 2020. Loop shares, listed

on Nasdaq, are down about 50% this year. Danone said it has

confidence in Loop's technology. Loop has also signed supply deals

with Pepsi and Coca-Cola's European bottler.

Less than a third of PET bottles sold in the U.S. are collected

for recycling, with less than 1% processed into food-grade plastic,

according to Pepsi, one of the biggest buyers. The bottled-water

industry says using more recycled plastic in bottles will

incentivize collection of old bottles by giving them value.

Companies are launching new marketing campaigns, employing more

waste pickers and backing new bottle deposit schemes to encourage

recycling.

Danone, like much of the industry, has made promises about using

recycled material before only to break them. A decade ago it

pledged to use 50% recycled plastic in its water bottles by 2009.

The very next year it slashed that target to between 20%-30% by

2011. Today, just 14% of the plastic in the bottles across its

brands is recycled material.

Other companies' efforts to broadly use recycled plastic have

also stagnated, even though a few produce 100% recycled PET bottles

for brands limited to certain countries or sizes. Nestlé's plastic

water bottles use just 5% recycled material in Europe and 7% in the

U.S., while Coca-Cola's use 10%. Pepsi says it uses 9% in bottles

in the U.S. and 16% in Europe.

In 2009, Nestlé launched a bottle made of 25% recycled plastic

at Whole Foods but later scrapped it. Danone yanked a Volvic bottle

made partly from biobased plastic after consumers paid little

attention.

Danone gained confidence after consumers in Argentina in 2015

took to a new bottle made of 50% recycled plastic. Advertisements

for the Villavicencio brand featured a popular actor explaining how

waste bottles are turned into new ones.

Danone sought to be more ambitious with Evian. "Once we put

ourselves in consumers' shoes we realized 25% or 50% doesn't make a

lot of sense," said Mr. Chauvelot. "What makes sense to the

consumer is 100%."

All Evian's water is bottled at a single plant on the outskirts

of the tranquil town that shares its name on the shores of Lake

Geneva. The brand traces its roots back to 1789 when a French count

claimed drinking the town's water cured his kidney disease.

Evian rolled out in the U.S. in the late 1970s, wooing

health-conscious Americans with splashy ads playing up the benefits

of hydration. By 1999, helped by clever product placement among

models and athletes, Evian was the world's No. 1 bottled-water

brand and the U.S. market leader by sales, according to company

filings.

Then a flood of competitors, including mass-market offerings

such as Coca-Cola's Dasani and upscale brands such as Fiji, grabbed

share. Evian's U.S. volumes plunged to 29 million gallons last year

from 69 million in 2000, according to Beverage Marketing Corp. Its

global market share by volume last year was 0.5% according to

Euromonitor.

Danone said marketing about the recycling plan helped Evian

sales climb 6% in the first nine months of the year.

At Evian's giant bottling plant on the French-Swiss border, five

trucks of virgin and recycled PET arrive each day. About 100 metric

tons of rice-like plastic pellets pour into towering metal

silos.

After being quality checked, the pellets are heated and molded

into test-tube shapes. Robots move these to sealed rooms where they

are blown into bottles, filled with water and capped. The fastest

of 10 lines can produce 72,000 bottles an hour. The plant has the

capacity to make two billion bottles a year.

To hit its recycling goal, Evian hopes to take deliveries of

Loop-branded plastics at the factory by 2020. It is also talking to

other potential suppliers. "We have a backup plan for sure," said

Mr. Jouin, Danone's packaging head.

Write to Saabira Chaudhuri at saabira.chaudhuri@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 12, 2018 10:33 ET (15:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

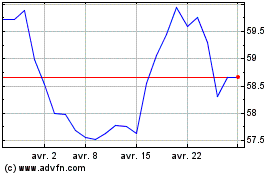

Danone (EU:BN)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

Danone (EU:BN)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024