Culp assures executives he'll leave the traditional structure

intact

By Thomas Gryta

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (October 8, 2019).

When Larry Culp gathered top General Electric Co. officers for a

summit north of New York City last month, the chief executive had a

message for them. He wasn't going to dismantle their company.

They could be forgiven for suspecting otherwise. The industrial

giant had been through tumult, including the pressured departure of

a 16-year CEO, the aborted 14-month stint of his successor, a long

slide in the stock and a gutting of the dividend. A finance chief

teared up in 2017 as he revealed problems that had lain hidden

inside a company once seen as the apex of American manufacturing

might.

Now it had a new CEO, an outsider known for running his previous

company as a collection of independent businesses orbiting a small

central staff.

He put up a slide showing two organizational extremes. On one

end was a top-down, centralized management structure, similar to

the way GE had operated for years. The other end, he said, would be

Berkshire Hathaway's Warren Buffett sitting with just a handful of

staff.

Mr. Culp said he had heard concerns from his lieutenants about

moving GE in the direction of a decentralized corporate structure,

as his predecessor seemed to be doing. Then he said he agreed with

the concerns -- and he wasn't going to do it.

It was the first time Mr. Culp, GE's first outsider boss in its

127-year history, laid out his vision to the executives atop the

conglomerate's power turbine, jet engine and other factories.

He told them he would be streamlining the operations at GE and

shrinking its bureaucracy. The 300,000-employee company had seen

its corporate layer balloon to 26,000 by the time Mr. Culp first

joined as a board member in 2018. So far, he has moved about half

of those corporate-level people into individual businesses and is

giving the business units more autonomy.

Yet, according to people familiar with the meeting, he said he

saw a significant role for a refocused corporate operation at the

industrial giant, leaving intact the structure that stretches back

to its 19th-century beginnings. Though headquarters will be

smaller, it will continue to oversee capital allocation, talent and

technology.

In short, Mr. Culp's plan is to fix GE instead of breaking it

apart, as some people inside and outside the conglomerate expected.

And in doing so, he is treating GE like any other company -- hiring

from the outside and importing management strategies. The question

is whether his deliberate approach will be enough to address GE's

big problems.

At the early-September conference, held at GE's leadership

academy in Crotonville, N.Y., Mr. Culp urged executives to be

candid about problems they encountered. It was an implicit

repudiation of the culture of optimism that insiders say defined GE

under former longtime CEO Jeffrey Immelt, which was dismissed by

some as "success theater." Mr. Culp has said he doesn't want

executives contorting to meet financial goals or please bosses.

From Mr. Immelt's mid-2017 resignation until a year ago, John

Flannery, a 30-year company veteran, led GE. The board approved Mr.

Flannery's plans to sell off the company's century-old locomotive

division, exit the oil and gas business and spin off the

health-care unit. Mr. Culp, named CEO in place of Mr. Flannery on

Oct. 1, 2018, largely stuck to that outline in his first year,

except he kept the part of health care that makes hospital

equipment and sold the biotech part to the company he previously

ran, Danaher Corp.

He has made other moves to reduce debt. On Monday, GE said it

would freeze its U.S. pension plan for about 20,000 salaried

employees and make other moves that would cut its net debt by up to

$6 billion.

One thing that hasn't changed much is GE's depressed share

price. The stock, which traded around $14 when Mr. Culp took over

and fell to near $6 in the market slump last December, has

languished below $10 for much of this year. The company's market

value has shriveled to roughly $75 billion from nearly $600 billion

in 2000.

While company veterans still run major business units, Mr. Culp

has hired outsiders for human resources, investor relations and the

digital business. He has said he would hire a new finance chief,

also expected to come from the outside. Surrounding himself with

new advisers, he fired longtime bankers who had overseen major

acquisitions in the power-turbine and oil markets that proved

disastrous.

He has continued to revamp the board, which before Mr. Culp's

tenure blessed the ill-fated deal-making as well as tens of

billions of dollars in stock buybacks performed when the shares

cost far more than they do now. Seven of the current 10 directors,

including Mr. Culp, have joined in the past three years.

Some of the moves are typical for an outside CEO coming to a

troubled company, but they run against GE's tradition of

cultivating its own talent.

The new CEO is bringing new tools for the job, such as his

adherence to lean-manufacturing practices, developed at Toyota

Motor Corp., which center on an approach known as kaizen. The

system focuses on seeking continuous improvement through in-depth

sessions to assess employees' progress. GE itself, In its glory

years, was considered the lodestar of management excellence.

Danaher, which Mr. Culp ran from 2001 to 2014, and which is far

smaller than GE, was among the first U.S. companies to adopt

lean-manufacturing practices, in the 1980s. That was a decade

before GE's celebrated former chief Jack Welch deployed Six Sigma,

another process-improvement system.

Now Mr. Culp has begun rolling out Hoshin Kanri, a Japanese

strategic-planning process that is part of lean manufacturing.

Hoshin Kanri holds that all workers should understand the company's

strategy and how their role can contribute to it, enabling feedback

and improvement to come up from lower levels.

Such programs seek to find small adjustments that will add up to

large change over time. They are an approach that might expose

lackluster operations, such as when Mr. Culp found that GE was

spending over $100 million a year on premium shipping services to

compensate for delays in getting orders out of factories on

time.

"The ironic thing is that most of what he has to do is

re-instill the cultural and managerial attributes that GE was

justly famous for until recently," said Martin Sankey, a senior

research analyst at investment-management firm Neuberger Berman,

which owns about two million GE shares.

Mr. Culp has increased oversight of GE's divisions, requiring

formal monthly reviews and encouraging daily management of

operations to get away from the end-of-quarter rush to make

financial targets. Earnings per share, once the most important

metric at GE, are viewed as a result that comes from managing the

operations.

At GE's Boston headquarters these days, there are constant

reminders a newcomer is in charge. For one thing, the CEO often

isn't around. He drops in on manufacturing plants, sometimes alone

and without warning, where he walks the floor to size up employees

and how they work.

Mr. Culp -- full name Henry Lawrence Culp Jr., and 56 years old

-- recently gathered top executives at GE's main power-division

plant in Greenville, S.C., for a weeklong teach-in on manufacturing

practices. The work led to streamlining inventory for part of the

assembly line for natural-gas turbines.

In May, he took GE Vice Chairman David Joyce, the leader of the

aviation business, to observe FedEx Corp.'s midnight sorting

process in Memphis, Tenn. The goal was to understand how GE's

aviation business fits into the operations of a customer.

Separately, Mr. Culp discovered a weekslong gap between the time

GE's Aviation division completed work and when its customers were

billed, he told investors earlier this year. He said GE has cut the

gap by a third.

Mr. Culp has spent much of the past year focused on the power

division, a $27 billion business that has been at the core of GE's

financial and operational problems. Saddled with excess gas-turbine

inventory after misjudging demand several years ago, the unit has

burned through billions of dollars as sales slid.

The power business is working through poorly structured deals

that were signed to grab market share. And securities regulators

are investigating how the division accounted for service contracts

and a $22 billion write-off related to the 2015 acquisition of

French company Alstom SA's power business.

In one of his first moves, Mr. Culp split the power division,

separating the gas-turbine and services division from the rest. He

has merged smaller operations into bigger ones, cut a thousand jobs

this year and pushed leaders to continually hone processes.

He wants GE to sign deals with better economics even if this

means passing on some business, and to make sure it delivers on the

agreements, such as by avoiding missed deadlines and penalties. He

has said it will take years to turn around the power division's

performance and work through its backlog of troubled contracts.

An internal probe two years ago found that in at least two

quarters, GE recorded sales of mobile power turbines to a customer

in Angola before they were transferred, according to people

familiar with the investigation. It found that nearly $100 million

of sales had been prematurely booked, usually just as a quarter was

ending, and needed to be moved to different periods, one of the

people said.

The accounting adjustments weren't disclosed because they were

deemed immaterial to a company with well over $100 billion in

annual revenue, according to those familiar with the review, who

added that the probe prompted changes to accounting policies.

Among executives questioned by internal investigators was Scott

Strazik, the CEO of the Gas Power division. Through GE, Mr. Strazik

declined to comment.

In late July, GE raised its cash-flow projections. Executives

said the power business wouldn't burn through as much cash as

feared.

The next month, the company faced an attack by Harry Markopolos,

an accounting expert working with a hedge fund short seller. Mr.

Markopolos's group issued a lengthy report questioning several

aspects of GE's accounting and claiming it was short on working

capital, sending its shares plunging 11% in a day.

Mr. Culp struck back, calling Mr. Markopolos's analysis flawed

and accusing him of market manipulation. GE said it was confident

its accounting was proper. Several major investors and Wall Street

analysts said they agreed with GE. The stock has recovered much of

the loss.

Ken Langone, a co-founder of Home Depot and former GE director,

lauded Mr. Culp's approach as similar to Mr. Welch's and said he

was impressed that Mr. Culp bought GE shares for his own account

after the Markopolos report knocked their price down.

His "priorities are spot-on," said Mr. Langone, who added he

recently bought GE shares for the first time in 14 years.

It may take time for other investors to bet on GE again.

Financial advisory firm Medley & Brown LLC in Jackson, Miss.,

is the sort of outfit that once would have had GE's stock in every

client portfolio because of its reliability and dividend.

Now it doesn't own any GE shares for client accounts, said

Julius Ridgway, a financial adviser at the firm, and few clients

ask about the former blue chip. "Nobody sits around and wonders why

I don't own something that has lost that much value," he said.

Write to Thomas Gryta at thomas.gryta@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 08, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

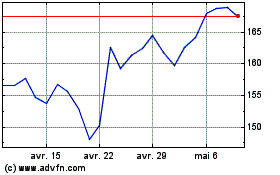

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024