By Matthew Dalton

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 26, 2019).

PARIS -- Tiffany & Co.'s underperforming operations are

about to get an overhaul from one of the world's most exacting

executives, French billionaire Bernard Arnault.

With LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SA's $16.2 billion

purchase of Tiffany, announced Monday, Mr. Arnault plans to pour

marketing resources into the high-end of Tiffany's jewelry line,

focusing attention on its high-carat diamond necklaces rather than

less-expensive silver jewelry. He also wants to launch new product

lines and improve the performance of Tiffany's far-flung network of

321 boutiques in more than 20 countries.

The chief executive is readying a playbook that he has used to

build some of the world's most successful luxury brands at LVMH,

now one of Europe's most valuable companies. His task is to

reinvigorate a storied brand that has been solidly profitable but

whose sales have stagnated in recent years. Comparable sales at

Tiffany have declined for two straight quarters because of a drop

in tourist spending in the U.S.

LVMH is paying all cash for Tiffany's shares and will finance

the deal by issuing bonds. Executives expect it to close in the

middle of next year following antitrust approval by the U.S., the

European Union and others.

Mr. Arnault's strategy calls for labels to benefit from LVMH's

deep pockets, sometimes for years, to make necessary investments.

Mr. Arnault said the purchase of the high-end jeweler Bulgari in

2011 offered a model for the Tiffany buy, requiring major

investments in marketing, boutique design and communications. Eight

years later, the brand's revenue has nearly doubled and its profit

has increased fivefold.

Because those investments take years to bear fruit, Tiffany is

better off inside LVMH, away from the glare of investors

scrutinizing the company's results, Mr. Arnault said. LVMH owns 75

brands, including luxury giants such as Louis Vuitton and Dior, but

doesn't disclose the performance of individual labels.

"We will plan long-term," Mr. Arnault said in an interview.

"Often with American brands traded on the stock market, the

emphasis is placed on the results of the quarter. It's not at all

the same strategic focus."

Mr. Arnault has also pioneered the use of distinctive

architecture in building boutiques, making them destinations for

well-heeled tourists around the world. Customers routinely line up

to get inside Louis Vuitton shops, some of which feature

white-glove service for top clientele.

Last month Mr. Arnault made a visit to Seoul to inaugurate a

Louis Vuitton boutique designed by architect Frank Gehry. Mr.

Arnault quietly took time to pop into a Tiffany boutique

nearby.

As Mr. Arnault browsed the store, he noticed the glass on a

display case was dirty and took a photo of it, telling his team

that it was an example of management failure, a person familiar

with the visit said.

"There are things that are terrific, and there are things that

must be improved," Mr. Arnault said in the interview, when asked

about the episode. "I look at the details."

Tiffany is set to receive such scrutiny on a permanent basis

once the deal is completed. Mr. Arnault regularly visits the

boutiques of his biggest brands in the French capital and on trips

abroad to inspect their operations.

"Each week I make notes, whether it's at Vuitton, Dior or other

brands," Mr. Arnault said.

Tiffany's boutiques are less profitable than those of Cartier

and Bulgari, its major competitors. To address that, LVMH could

tighten its retail network in the U.S., where it has more than 100

stores, says Erwan Rambourg, an analyst at HSBC. Those stores tend

to sell the brand's less expensive jewelry.

Or it could boost efforts to attract Chinese shoppers, who tend

to be more profitable clientele than their Western

counterparts.

"Tiffany is under-indexed with the Chinese," Mr. Rambourg says.

"The Chinese consumer really likes Tiffany but obviously you need

to invest more to develop the awareness."

Despite the problems that struck him in Seoul, Mr. Arnault sees

a huge advantage in Tiffany's retail network: The brand sells

almost exclusively through its own stores, not department stores or

other third parties.

Mr. Arnault frowns on his brands selling wholesale, although

some of the company's smaller ones do. That relinquishes control

over pricing, allowing independent retailers to sell at a discount,

and the look of stores where the brands' wares are displayed.

Louis Vuitton and Dior, for example, sell almost exclusively

through their own stores. Louis Vuitton never holds sales. And both

brands gain intimate knowledge of their clients' spending habits,

data that would be collected by the independent retailer if those

brands didn't rely on directly operated stores.

"Tiffany is in direct contact with its clients. It's one of the

few jewelry brands in that position," Mr. Arnault said. "This is a

fantastic benefit."

Mr. Arnault says that he expects Tiffany to boost LVMH's

operating profit -- EUR10 billion in 2018 -- by around EUR500

million (about $550 million) in the first full year the jeweler is

included in its results. The acquisition will be financed by

issuing bonds at ultralow interest rates now available to LVMH of

less than 1%.

Write to Matthew Dalton at Matthew.Dalton@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 26, 2019 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

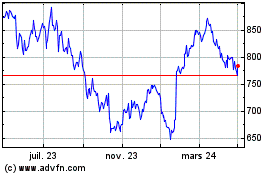

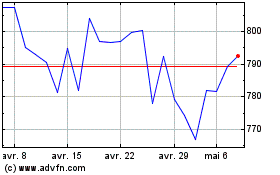

Lvmh Moet Hennessy Louis... (EU:MC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

Lvmh Moet Hennessy Louis... (EU:MC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024