By Adam Janofsky

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency uses

facial-recognition software at airports to identify impostors.

Stadiums and arenas use it to enhance security. Law-enforcement

agencies deploy it to spot suspects.

But as the technology has become more widespread -- from

catching shoplifters at malls to presenting consumers with targeted

ads -- critics are questioning whether it threatens privacy and

whether it is accurate enough to be reliable.

"The ultimate nightmare is that we lose all anonymity when we

step outside our homes," says Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst

for the American Civil Liberties Union. "If you know where everyone

is, you know where they work, live, pray. You know the doctors they

visit, political meetings they attend, their hobbies, the sexual

activities they engage in and who they're associating with."

These concerns led San Francisco last month to ban the use of

facial-recognition tools by the police and other city agencies.

Other cities, including Somerville, Mass., and Oakland, Calif., are

considering similar laws.

The escalating push to regulate the technology has also reached

Congress, which held a hearing on the topic on June 4, the second

such discussion in two weeks. The ACLU, meanwhile, is developing a

step-by-step playbook for communities interested in setting

restrictions on facial-recognition systems.

"You've now hit the sweet spot that brings progressives and

conservatives together," Rep. Mark Meadows (R., N.C.) said at the

first hearing on May 22.

"That's music to my ears," Rep. Elijah Cummings (D., Md.)

responded.

"I was hopeful this would spark a conversation about the

pernicious misuse of technology, and to my pleasure it has not only

sparked a statewide conversation but a national one," says Aaron

Peskin, the San Francisco supervisor who led the city's effort.

About a dozen state and city lawmakers from around the country have

reached out to him for information and advice, he says.

Pushing for regulation

As these regulation efforts gain momentum, though, they face

strong opposition.

For one thing, law-enforcement groups argue that the technology

is a valuable tool for identifying suspects and efforts to ban it

could leave many crimes unsolved.

The groups have already won some concessions. For instance, Mr.

Peskin says that he added a handful of amendments to San

Francisco's bill after negotiations with law-enforcement

advocates.

At the same time, some makers of facial-recognition technology

are working with legislators to propose weaker bills. Microsoft,

for example, was involved in crafting a failed Washington state

proposal that would have put several limits on facial recognition

without calling for a ban, among other things.

Still, critics argue that strong restrictions are necessary to

protect privacy and civil rights. And they're pushing a number of

different types of regulations to reach their goal.

Some advocacy organizations argue that facial-recognition

technologies reinforce bias in the criminal-justice system and are

likely to be used to target certain communities. The technologies

could also lead to many incorrect arrests in certain communities,

critics argue: Researchers have documented how some

facial-recognition systems are more likely to misidentify people

with dark skin, for instance.

So, some civil-rights groups are proposing regulations that

would require makers of facial technology to have it independently

tested for accuracy and bias.

A broad coalition of nonprofits are working together to support

bills limiting the use of biometrics, such as AB-1215 in

California, which would prohibit the use of facial recognition for

data collected by police body cameras.

Another major issue for advocates is consent. Some proposed

bills would require organizations that use facial-recognition

technology to obtain people's consent before using the technology

on them.

Organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation are

opposing bills with what they see as weak rules, such as requiring

businesses to post signs that they're using facial-recognition

technology instead of requiring opt-in consent or banning the

technology altogether, says EFF senior staff attorney Adam

Schwartz.

But before those ideas make it into law, they must overcome

questions about how exactly they might work in practice.

Take the consent issue. "That simply doesn't make sense in many

places," says Daniel Castro, vice president of the Information

Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based

think tank. "Stores want to use this technology to catch

shoplifting. A shoplifter is not going to opt in."

Stadiums, hotel lobbies and other spots may also present

logistical problems, says Alan Raul, partner at law firm Sidley

Austin LLP and former vice chairman of the White House Privacy and

Civil Liberties Oversight Board.

Consent will likely need to be contextual, with certain large

venues requiring signs that inform people that facial-recognition

software is being used, instead of obtaining permission from every

customer, he says.

Still, there is at least one major facial-recognition system in

place that uses consent. The U.S. Customs and Border Protection

agency, which has been developing facial-recognition systems for

airports since 2013, gives arriving and departing U.S. citizens the

option of doing a manual verification of identity instead of a

facial-recognition scan. (The agency also uses a manual

verification if its recognition system spots a potential

impostor.)

Another potentially thorny issue in the regulation effort:

Lawmakers may find it difficult to agree on what exactly facial

recognition is and what they are trying to regulate, says Clare

Garvie, a researcher who studies facial recognition at the Center

on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law.

For example, eye-tracking technology that analyzes what

advertisements people pay attention to, or face-scanning tools that

gauge emotional reactions without identifying individuals, make

facial recognition hard to define.

"Facial recognition encompasses a wide array of possible

technologies, and you don't want regulations to be so broad that it

effectively regulates nothing," she says.

The record so far

Currently, three states have passed bills to protect people's

biometric privacy. One -- Illinois's Biometric Information Privacy

Act, passed in 2008 -- requires companies to get consent before

collecting biometric data, including face scans.

The law has led to a wave of class-action lawsuits alleging that

companies didn't obtain consent -- a result that has likely given

other states pause over enacting similar legislation, says Ms.

Garvie.

Bills in Texas and Washington have similar privacy provisions,

but allow only state attorneys general to sue for violations. And

Washington's law doesn't include facial-recognition data in its

definition of biometric information.

As lawmakers and activists wrestle with regulatory issues, some

critics say there should be a moratorium on the technology until

concerns are addressed and the public forms a consensus on what

guardrails are appropriate.

But those efforts might backfire if people view it as a

crackdown on a technology that can help prevent crime, says Mr.

Raul.

For example, 41% of people said they favored using

facial-recognition software in schools to protect students,

compared with 38% who found it unfavorable, according to a

September Brookings Institution survey of 2,000 people in the U.S.

Half of the respondents said they didn't favor the use of facial

recognition in stores to prevent theft, and 44% said they didn't

favor it in airports to establish identity and in stadiums to

improve security.

"The technology has so many beneficial uses that it's hard to

see the public will feel comfortable stopping something that will

be useful in deterring, investigating and apprehending criminals,"

says Mr. Raul.

Mr. Janofsky is a reporter for WSJ Pro Cybersecurity in New

York. He can be reached at adam.janofsky@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 04, 2019 22:20 ET (02:20 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

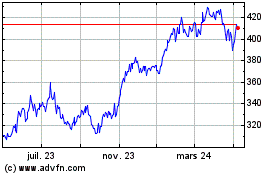

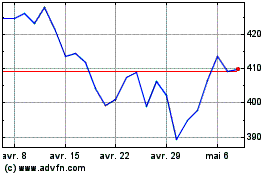

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024