By Sarah E. Needleman

False and misleading information is spreading in new ways across

social media, as people seeking to influence political campaigns or

achieve illicit goals attempt to stay ahead of platform operators

trying to stop them.

The new methods range from employing real people -- instead of

relying solely on bots -- to post messages that appear authentic

and trustworthy, to sharing fabricated images, audio and video,

researchers say.

Purveyors of disinformation are experimenting with these

techniques largely because Twitter Inc., Facebook Inc. and other

social-media companies have beefed up efforts to squash their

campaigns, though some critics want to see the companies do

more.

The companies began sharpening their focus on coordinated

campaigns intended to sway public opinion after the identification

of Russian government interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential

election. A report from a U.S. Senate committee released earlier

this month criticized U.S. tech giants for helping spread

disinformation during the 2016 campaign and called for better

coordination of efforts to prevent similar activity for elections

in 2020.

"People think it's a problem that can be fixed," says Nathaniel

Gleicher, head of cybersecurity policy at Facebook. "But we know

these actors are going to keep trying. That's the one guarantee we

have."

Lee Foster, an analyst at cybersecurity firm FireEye Inc., says

manipulators are also changing their tactics because the public has

become more aware that disinformation operations are carried out on

social media. Mr. Foster was part of an investigation into a

coordinated disinformation campaign on Facebook, Twitter and other

large social-media platforms last year believed to promote Iranian

interests.

A veneer of truth

Interest groups, governments, companies and individuals are

motivated for several reasons to spread disinformation, according

to researchers. Some are looking to promote a political agenda or

ideological position, while others want to draw social-media users

to a website so they can generate advertising or other revenue. In

some cases, the messages dispersed are merely pranks carried out

for entertainment purposes.

The results of these efforts can be significant, with the

potential to distort elections, divert attention from other

societal issues or instill fear. They can also be deadly. Last

year, more than 20 people were killed in India by mob violence

after false rumors about child-trafficking activity spread on

Facebook's WhatsApp messaging service.

Increasingly, people seeking to spread disinformation are

becoming less reliant on bots to flood platforms with messages,

having humans behind keyboards do the work instead, researchers

say. They say organizers are paying people who have large online

followings to amplify their messages without disclosing the

transactions.

Campaign organizers are also taking over dormant accounts under

new guises and encouraging people to post messages in support of

their cause, researchers say. These organizers, in many cases,

obscure their identities and intentions and can dupe users into

spreading false information through their networks.

"You have less bot activity and now people publishing multiple

times a day," says Claire Wardle, director of First Draft, a

nonprofit that supports research into disinformation campaigns on

the internet and is funded in part by Alphabet Inc.'s Google, as

well as Facebook and Twitter. "They're using other people already

very passionate about certain issues to push weaponized

content."

For example, ahead of the 2017 French presidential election, a

group of Marine Le Pen supporters sought to promote her campaign by

simultaneously posting tweets with the same hashtag and had bots do

the same, according to Ben Nimmo, head of investigations at New

York-based Graphika Inc., a social-media-analytics firm. With this

approach, people are looking to give the false impression that

their posts have gone viral organically, which can help them in

turn attract coverage by legitimate news outlets, he says.

Hashtags such as #LaFranceVoteMarine and #Marine2017 began

trending on Twitter across France, raising Ms. Le Pen's profile by

gaining coverage from French media that portrayed her supporters as

powerful and effective online.

"It was a lot more sophisticated than just turning on a bot

army," Mr. Nimmo says.

Also, rather than solely pumping out falsehoods, organizers are

mixing truth with deceptive content on the larger social platforms

-- or with inflammatory content on smaller ones that have looser

content controls such as Gab and 4chan -- to gradually build up

followers and make themselves appear more credible, researchers

say. For instance, a real photo may be posted on these smaller

sites with a highly sensationalized or misleading caption to

inflame social divisions.

"Gab allows all protected political speech, no more, no less,"

said Andrew Torba, chief executive of the social network, in a

statement. Representatives for 4chan didn't respond to a request

for comment.

Fake images and audio

So-called deep fakes -- phony images, video or audio created

with artificial intelligence -- are another new tool used to

deceive social-media users, researchers say. These differ from

already common "cheap fakes" -- deceptive alterations of real

content, such as the doctored video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi

(D., Calif.) that went viral on YouTube and Facebook in May.

"Deep fakes are worrisome because they are very hard to detect

by the lay public and journalists alike," says Joan Donovan,

director of research at Harvard University's Shorenstein Center on

Media, Politics and Public Policy. "Looking forward to 2020, these

newer tactics are going to be difficult to manage and defend

against."

Another concern, says FireEye's Mr. Foster, is that people will

claim video or audio of them acting badly is a deep fake, even when

that isn't the case. "Their mere existence will provide plausible

deniability for the actions or comments that real people do make,"

he says.

Such new techniques are coming into play as coordinated attacks

are expanding geographically, originating from 70 countries this

year as of September, up from 48 in 2018 and 28 in 2017, according

to a study by researchers at Oxford University. The findings also

show that 47 countries have used state-sponsored groups to attack

political opponents or activists so far this year, nearly double

the number from last year.

Platforms fight back

Facing mounting pressure from governments and public outcry,

social-media companies have worked to thwart platform manipulation.

Twitter and Facebook, for example, have suspended tens of millions

of accounts affiliated with disinformation campaigns across the

globe, while Reddit Inc. this year said it removed more than 10.6

million accounts with compromised login credentials.

The companies have also ramped up hiring of staff dedicated to

spotting coordinated attacks. Facebook said it now has 30,000

employees focused on user safety and security, three times as many

as it had 18 months ago. But liberal- and conservative-leaning

politicians and interest groups as well as free-speech advocates

have panned social-media companies in recent years for either

dragging their feet on content-moderation controls or going too far

to alter genuine discourse. In a speech at Georgetown University

earlier this month, Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg said

the company must continue to stand for free expression even though

it has worked to remediate concerns about misinformation and hate

speech on the social network.

Social-media companies also have been sharing data they have

collected on coordinated attacks with researchers. Some companies

have also created deep-fake videos to help researchers develop

detection methods. Facebook earlier this year teamed up with

several partners including Microsoft Corp. to launch a contest to

better detect deep fakes. Mr. Gleicher of Facebook says the spread

of false and misleading information on social media is too

difficult for any one company to tackle alone.

That said, companies need to be cautious when they share

information about coordinated attacks with the public to avoid

giving people insight into how to game the system in the future,

says Yoel Roth, head of site integrity at Twitter.

Social-media firms also don't want to inadvertently inflate the

magnitude of manipulation campaigns by disclosing too many details

about how they occur, Mr. Gleicher says. "Sophisticated actors try

to make themselves look more powerful than they are," he says.

Ms. Needleman is a Wall Street Journal reporter in New York. She

can be reached at sarah.needleman@wsj.com .

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 24, 2019 19:17 ET (23:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

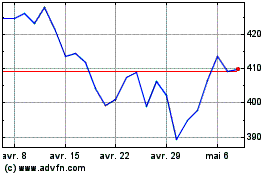

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

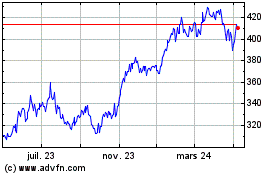

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024