On-Demand Warehouse Space Gains Traction in Tight Real-Estate Market

23 Décembre 2018 - 3:29PM

Dow Jones News

By Jennifer Smith

Some big retailers are looking to become as flexible as

short-term apartment renters when it comes to managing

warehouses.

This holiday season, Walmart Inc. used Flexe Inc., a

Seattle-based marketplace that connects warehouse operators with

businesses in need of storage, to secure about 1.5 million square

feet of temporary space to handle the mounting demands of

e-commerce fulfillment.

The warehouse operators that Walmart found through the platform

handle hiring and other administrative tasks for the pop-up spots,

spread out across three facilities in Pennsylvania, Illinois and

Nevada, and Walmart avoids paying year-round for space it would

only use during peak season.

Known as on-demand warehousing, the idea is to tap into unused

space in a crowded U.S. industrial real-estate market where

distribution centers near population centers are fetching a growing

price premium. Retailers and manufacturers are trying to position

goods closer to customers without getting locked into long-term

contracts or multiyear leases when rapid changes in buying patterns

and trade conditions have made forecasting demand more

difficult.

Walmart's biggest volumes come from Thanksgiving to Christmas,

Justin Schuhardt, senior director of operations for Walmart

e-commerce, said at an industry conference earlier this year. "You

don't always want to build the church for Easter."

Flexible warehousing startups often pitch their services as a

way for midsize retailers and online startups to compete with

Amazon.com Inc. without having to build their own distribution

networks.

But larger companies are taking an interest, including those

with established logistics operations.

Retailers and manufacturers are using such pay-as-you go

arrangements to cope with everything from hurricanes to global

trade tensions. Ace Hardware Corp., for example, used Flexe to

stage generators and other disaster-relief items during the 2018

hurricane season after scrambling last year to get supplies to

regions damaged by Hurricanes Harvey and Irma.

The interest comes as growing e-commerce sales sharpen

competition for warehouse space and push up prices. The industrial

availability rate fell to 7.1% in the third quarter, its lowest

since 2000, according to real-estate brokerage firm CBRE Group

Inc.

Companies don't want to commit to multiyear contracts "without

knowing how consumer demand is going to shake out," said Adam

Mullen, who leads CBRE's industrial and logistics business for the

Americas. "They know they are going to see peaks and valleys, and

they're tired of making investments over the whole year."

The strategy is also a way to address the uncertainty from

global trade tensions. Stord Inc., an Atlanta startup with a

network of more than 250 warehouses across the U.S., helped a

Chinese solar-panel supplier temporarily expand its New Jersey

storage capacity by fivefold earlier this year when the Trump

administration imposed stiff levies on foreign-made solar

panels.

"The tariffs were hitting, and so they were trying to bring in

248 containers all at once, all of a sudden," Stord Chief Executive

Sean Henry said.

No single warehouse in the company's network near the Port of

New York and New Jersey could accommodate the surge on just two

weeks' notice. So Stord, which also helped arrange trucking from

the port, split the goods between three locations, eventually

shifting all the client's inbound product to a shared facility

operated by Seldat Inc. in Burlington, N.J.

Fast-food chain KFC used a British warehouse-renting service

called Stowga to help line up replacement facilities in the U.K.

after supply-chain problems with Deutsche Post AG's DHL and another

provider disrupted chicken deliveries to hundreds of

restaurants.

"They needed eight warehouses. We typed into the search and we

had them instantly," Stowga founder and Chief Executive Charlie

Pool said. Stowga provides a standardized contract and charges

warehouse operators for listings, but unlike some U.S. warehouse

platforms, doesn't get involved in operations.

A spokesman for KFC U.K. confirmed the company used Stowga as

part of its recovery efforts, and said restaurants there have been

back up and running with a full menu since May. DHL declined to

comment.

Facilities known as public warehouses have offered space on a

short-term basis for years. But many of the new on-demand platforms

offer a high-tech twist, incorporating software that simplifies the

cumbersome process of integrating the customer's order management

technology with the provider's systems.

With the overall market for public storage and warehousing

projected to hit $28.7 billion by 2023, according to researcher

IBISWorld, more companies are piling in.

In April XPO Logistics Inc., one of the largest logistics firms

in North America, launched a flexible distribution service that it

expects to generate $1 billion in revenue over the next few

years.

Delivery giant United Parcel Service Inc. launched its own

warehouse platform in August, an offering called Ware2Go that

matches companies with vetted fulfillment providers. The offering

was designed for small to medium-size merchants, though larger

companies also have used the service, UPS said.

Write to Jennifer Smith at jennifer.smith@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 23, 2018 09:14 ET (14:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

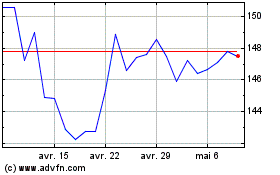

United Parcel Service (NYSE:UPS)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

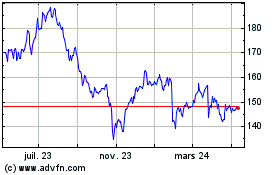

United Parcel Service (NYSE:UPS)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024