By James R. Hagerty

Simon Ramo made his mark in aerospace history in the 1950s as a

leader of the U.S. race against the Soviet Union to build missiles

capable of flashing nuclear weapons around the world. He lived

another 60 years, giving him time to develop spacecraft, write or

co-write more than 60 books, advise the White House on technology

and play his violin.

Among friends, who knew him as Si, he was admired for his quick

wit. At an early missile test, one of the rockets toppled over

after rising only about 6 inches. "Well," he is said to have

quipped, "now that we know the thing can fly, all we have to do is

improve its range a bit."

Dr. Ramo died June 27 at his home in Santa Monica, Calif. He was

103 years old.

Dr. Ramo was a co-founder of TRW Inc., an aerospace and

auto-parts company sold to Northrop Grumman Corp. in 2002. Among

his many accolades was the Presidential Medal of Freedom, awarded

by President Ronald Reagan. He joined in violin jam sessions with

masters including Jascha Heifetz. At age 100 he earned his final

patent, for educational software.

Ever curious, Dr. Ramo would start researching a new topic, "and

the next thing you know he's writing a book about it," said Ronald

Sugar, a longtime friend. While Dr. Sugar was chief executive of

Northrop, he got a call from Dr. Ramo proposing that the two should

collaborate on a book about business forecasting.

"Si, I'm kind of busy right now," Dr. Sugar recalled saying. Dr.

Ramo wouldn't be put off. He immediately sent Dr. Sugar a draft and

told him to feel free to make changes or additions.

After buying TRW in 2002, Northrop called on Dr. Ramo to

reassure nervous TRW employees. "I'm the R in TRW," he told them,

"and I'm really very happy that there are three Rs in Northrop

Grumman." That quip "defused all the angst in the room," said Kent

Kresa, then CEO of Northrop.

Dr. Ramo was never short of ideas for how to reorder the world.

In his book "Cure for Chaos," he explained how to organize a

"systems approach" to mobilize the expertise of many specialists to

address problems holistically, rather than piecemeal. He argued

that the U.S. had learned to use that approach for weaponry and

consumer goods but not to do such things as improve hospitals or

create efficient mass transit.

In two books on tennis, he explained how even a so-so player

could win. One tip: Praise your opponent for making a shot that

lands just inside the line. The overconfident opponent may then

lose points trying to repeat the trick.

In his book "Meetings, Meetings, and More Meetings," Dr. Ramo

estimated he had devoted 10 years of his life to them. He once

described himself as a "professional meeting goer-toer." His advice

for meeting organizers was to invite only people essential to

advancing the agenda.

Dr. Ramo saw humor as a vital management tool. For leaders

lacking a funny bone, he suggested studying books of witty remarks.

He recommended "The 2,548 Best Things Anybody Ever Said" by Robert

Byrne. Yet he advised against trying too hard to be funny and said

that "if the joke starts with 'a minister, a priest and a rabbi...'

don't tell it."

Simon Ramo was born May 7, 1913, and grew up in Salt Lake City.

His father, who had immigrated from Brest-Litovsk, then ruled by

Russia, ran a men's clothing store. Young Simon spent his college

savings on a $325 violin, betting correctly that it would help him

win a musical contest and gain a scholarship at the University of

Utah. He studied engineering there.

At age 23, he earned a doctorate in physics and electrical

engineering at the California Institute of Technology.

General Electric Co. hired him as a researcher in Schenectady,

N.Y., in 1936 -- partly, he said, for his violin skills. (GE

supported the symphony orchestra in Schenectady and supplied some

of its musicians.)

In the lab, "they let me do whatever I wanted," he recalled. Dr.

Ramo worked on generating microwaves, or "extremely high-frequency

electrical phenomena," as he described them. That led him to the

field of radar, where he did military-related work at GE during

World War II.

After the war, he joined Hughes Aircraft Co., where he created a

defense-electronics business. Concluding that the company's owner,

Howard Hughes, was too eccentric for dealings with the Pentagon,

Dr. Ramo and a friend from his Caltech days, Dean Wooldridge, split

off in 1953 to form their own defense-electronics company,

Ramo-Wooldridge, later TRW. Their first office was a former

barbershop in Los Angeles. The Pentagon soon hired Dr. Ramo and his

new firm to coordinate development of an intercontinental ballistic

missile, dubbed the ICBM.

The arms race was on. As Dr. Ramo wrote later, "A surprise

strike by a large fleet of Soviet ICBMs carrying nuclear bombs

could destroy the U.S. in half an hour." Some early U.S. test

missiles blew up or swerved crazily off course. By the late 1950s,

though, the missiles were reliably hitting targets more than 5,000

miles away. Dr. Ramo judged that the U.S. was "safely ahead" of the

Soviets, at least temporarily.

He already was guiding TRW into a new field, spacecraft. After

retiring from TRW in 1978, Dr. Ramo became an all-round sage and

author.

Dr. Sugar, the former CEO of Northrop, often lunched with him in

the 1990s at the Los Angeles Country Club. Dr. Sugar said he was

eager to hear Mr. Ramo talk about the history he had lived through,

but "all Si really wanted to talk about was the future." One topic

he liked was the potential for robots to replace soldiers -- the

subject of his 2011 book "Let Robots Do the Dying."

Dr. Ramo is survived by two sons, Jim and Alan, four

grandchildren and three great grandchildren. His wife, Virginia,

died in 2009.

Write to James R. Hagerty at bob.hagerty@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 08, 2016 11:11 ET (15:11 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

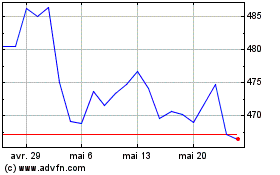

Northrop Grumman (NYSE:NOC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

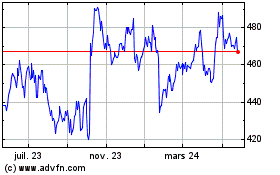

Northrop Grumman (NYSE:NOC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024