Scientists Search for Best Way to Restore Oysters in Chesapeake Bay

03 Août 2019 - 1:59PM

Dow Jones News

By Acacia Coronado | Photographs by Greg Kahn for The Wall Street Journal

Scientists are racing to stem a rapid decline in the oyster

population in Chesapeake Bay.

The number of oysters, a valuable part of the shellfish industry

in the region, has fluctuated and been unreliable since the 1980s.

The amount of market-size mollusks harvested in the Maryland

stretch of the bay fell from about 380,000 bushels in the 2015-16

season to 180,000 bushels in the 2017-18 season, according to state

data.

Water pollution, parasites and overfishing are among the reasons

behind the decline, scientists say. Also, heavy rains can increase

the flow of fresh water into bays, lowering water salinity and

making it uninhabitable for oysters.

"The current population baywide of oysters is estimated to only

be a couple percent of what were here in colonial times," said Will

Baker, president of the advocacy group Chesapeake Bay Foundation,

citing recent studies.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is one of several local, state and

national organizations working to restore oyster populations in the

area. One of its goals is to replenish oysters to the bay by

placing hatchery-produced seed oysters in sanctuary reefs.

About 32 million pounds of U.S. oysters worth more than $236.4

million were harvested in 2017, a decrease of nearly 1.5 million

pounds from the previous year, according to the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration. About 15% of the 2017 haul was from

the Middle Atlantic region, which includes the Chesapeake Bay.

In addition to the shellfish industry, oysters are essential to

the estuary ecosystems in which they live because they filter

water, removing excess algae and converting it to food. Oyster

reefs also are a magnet for a variety of other marine species.

The Sustainable Oyster Population and Fishery Act of 2016

required Maryland's Department of Natural Resources, in partnership

with the University of Maryland, to conduct a study and adopt a new

oyster management plan by 2018.

Dr. Michael Wilberg, professor at the University of Maryland

Center for Environmental Science and an author of the state's 2018

oyster stock assessment, said oyster populations tend to oscillate.

In addition to disease, contamination and harvesting, the rate of

oyster reproduction varies. For example, oyster populations

recovered after a dramatic hit from disease in the early 2000s.

The current population and habitat monitoring process costs more

than $7,000 a day and requires sending a professional diver into

dangerous underwater territory, which limits the amount of reefs

that can be assessed. Scientists said because of the time and

monetary cost of getting information, they are unable to

consistently track data from every section of oyster habitat.

"Getting information from that system is very challenging

because we are not underwater creatures," said Allison Colden,

Maryland fisheries scientist with the foundation.

The foundation is working with global aerospace and

defense-technology firm Northrop Grumman Corp. to develop new

remote-sensing technology to track oyster populations and the

health of oyster reefs in the bay. The new process will include

capturing underwater imagery, mapping the reefs and collecting

water chemistry -- without underwater divers.

R. Eric Reinke, chief science officer at Northrop Grumman, said

six teams within the company are competing to come up with the best

new technology, with the goal to start testing in early 2020. The

company, which is based in the Baltimore area, has partnered on

environmental education and preservation efforts for about 15

years.

"We're here to help the CBF reach its goal of planting 10

billion new oysters by 2025," Mr. Reinke said. "We have thousands

of employees in the state of Maryland and consider the Chesapeake

Bay part of our backyard."

Restoration efforts in the past 20 years have included placing

oyster shells into habitats where new oysters can use them to grow

and building concrete columns that reinforce oyster reef

structures, said Doug Myers, senior scientist in Maryland for the

Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

Ms. Colden said once the new technology is ready, one main goal

is to use it to assess what techniques have worked effectively and

to identify which locations in Maryland and Virginia need the most

work.

"This is not a short-term goal, restoring oysters in the

Chesapeake Bay will take a while," Ms. Colden said.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 03, 2019 07:44 ET (11:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

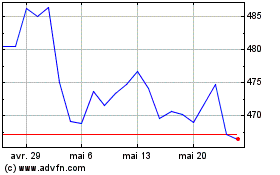

Northrop Grumman (NYSE:NOC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

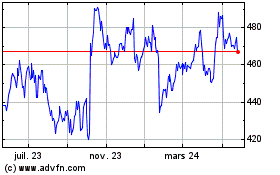

Northrop Grumman (NYSE:NOC)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024