By Kejal Vyas | Photographs by Joana Toro for The Wall Street Journal

GEORGETOWN, Guyana -- Along the sea wall separating this sleepy

capital's moldering wooden houses from the coffee-colored Atlantic,

construction workers in hard hats rush to expand ports, build

luxury condos and open the country's first Hard Rock Café.

The developments aim to tap the expected wealth from what until

recently was unimaginable for this jungle-covered former British

colony: oil.

An Exxon Mobil Corp.-led consortium said last week it has begun

offshore drilling after recently discovering at least 3.2 billion

barrels of light crude in Guyanese waters. Guyana is projected

within a decade to pump nearly a barrel of oil per person a day,

more per capita than Saudi Arabia. That makes this poor backwater

of 800,000 people -- mostly descendants of African slaves and

indentured laborers from India -- a top global energy frontier.

"Each Guyanese is going to be a U.S.-dollar millionaire, or

worth that, in a few years," Natural Resources Minister Raphael

Trotman said, referring to a national wealth fund the country is

developing.

Not everyone is convinced of a bonanza.

Many Guyanese say Exxon's deal disproportionately benefits the

company and its minority partners -- Hess Corp. and China's Cnooc

Ltd. -- while leaving little for this country of miners and farmers

on horse-drawn carts. Others worry about corruption and Guyana's

ability to responsibly handle an oil deposit worth nearly 50-times

the nation's gross domestic product.

"Boy, ain't nobody here getting rich when all everyone does is

steal," said Eon Samuels, 25, an unemployed construction worker, as

he fished from a pier.

Exxon has called Guyana one of its most important and

potentially profitable prospects, among a handful of new

developments the company has identified as the best since its

merger almost 20 years ago with Mobil Corp. Western oil companies

have increasingly turned to Latin America at a time when

opportunities have narrowed in other regions such as Russia or Iran

due to sanctions or resource nationalism.

Exxon said that Guyana will receive an estimated $1.6 billion in

royalties and revenue in the first five years after oil pumping

begins in 2020 and a projected $7 billion during the life of one of

its most promising fields. But the company hasn't finished

appraising all the oil that it has found and keeps discovering

more, portending what the company said was a larger payout for

Guyana down the road. "This emerging industry has the potential to

transform the economy of Guyana and positively impact the lives of

people for generations to come," a company spokeswoman said.

It isn't uncommon in the oil industry for the first investors to

get the best deals because they assume more risk. Exxon didn't

discover oil in Guyana until 2015, 16 years after it signed an

exploration contract.

But critics said the government should have demanded better

terms when Exxon renewed the contract in 2016.

"Exxon took advantage of our weak bargaining position and our

inexperience, and they were able to extract everything they

wanted," said Anand Goolsarran, the country's former auditor

general.

The International Monetary Fund, which is advising Guyana,

recently recommended that the government halt granting new licenses

until it can secure better terms and overhaul its tax

structure.

Under its deal, Exxon is permitted to use as much as 75% of

annual oil proceeds to recoup exploration and production costs once

commercial pumping begins. Guyana gets a 2% royalty of the proceeds

plus 50% of the remaining proceeds. That is on par with the world

average for "frontier exploration," said IHS Markit analyst Carlos

Bellorin.

But the oil companies' local taxes are paid from the country's

share of the profits, cutting into Guyana's take.

"We will suffer from that contract for the next 75 years," said

Christopher Ram, a prominent Guyanese attorney who through a weekly

newspaper column and speeches has become a vociferous critic of the

oil deal. "But what do I know? I'm just a third-world bookkeeper,"

he added, sifting through pages of the deal with Exxon.

Guyanese officials acknowledge the terms with Exxon aren't ideal

but they point to other benefits for an isolated, underdeveloped

and thinly populated country that suffers from tensions between its

two main ethnic groups. They say the country needs Exxon's

international lobbying might in a territorial tussle with

neighboring Venezuela, which nationalized Exxon's assets a decade

ago before a court ordered it to pay the company $1 billion.

Guyana's government says that an $18 million signing bonus from

Exxon will pay the country's legal fees, as President David

Granger's government tries to resolve Venezuela's century-old

border claim on two thirds of Guyana's land and maritime territory

-- including areas where Guyana wants to drill -- that has stymied

foreign investment.

We need companies that have international influence in the

corridors of power...so those things come at a price," said Mr.

Trotman, the resources minister. "If we were an ordinary

jurisdiction, I would say our terms look awful. But we have existed

always with a threat of force against us. We have had to make

decisions that are in our best national interest."

Foreign Minister Carl Greenidge, who is courting foreign oil

companies such as France's Total and Spain's Repsol, said the

concerns are overblown. He said the government is preparing to

spend wisely, with lawmakers working on a sovereign-wealth fund to

invest oil earnings in a country with average incomes of about

$4,000 a year.

"I'm tired of people calling this the apocalypse," Mr. Greenidge

said. "There are people here who think oil is just a rumor, a fraud

by Exxon. They're mixing black magic with economics."

Few Guyanese will ever see the oil, which will be extracted 150

miles offshore and loaded onto floating storage vessels before

being sold directly into the market. Onshore, the oil prospects

have spawned a rush of construction activity.

At the Muneshwers Ltd. wharf here, one of Guyana's biggest

container yards, workers rushed recently to expand a port area

where Exxon's supply vessels are loaded for offshore platforms.

Last year, Project manager Rabin Chandarpal had orders to

accommodate one supply ship a week. Now he needs space for four

ships a week.

"The more oil they find out there, the more activity we see

here," Mr. Chandarpal said.

The Pegasus Hotel, one of Georgetown's most prominent, is

planning a $100 million expansion that includes a new 15-floor

convention center. The Trinidadian company MovieTowne is building

an office-space and retail complex that will house eight new

cinemas.

But concerns remain. Some worry that the production of oil will

impact traditional Guyanese agriculture such as rice and sugar.

"I just ask, 'Where are we headed?'" said Somar Gharan, 62, who

works at a sugar mill. He fears Guyana could become like oil-rich

Venezuela.

Another sugar mill worker, Glenroy McKenzie, was sanguine.

"In the next 20 years," he said, "maybe my daughter will be

working on one of those platforms. I have a lot of hope."

Write to Kejal Vyas at kejal.vyas@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 21, 2018 12:20 ET (16:20 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

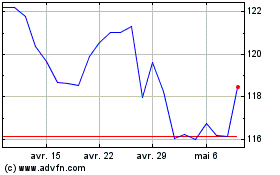

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024