Falling Crude Prices Test Big Oil's New Financial Discipline

29 Novembre 2018 - 1:36PM

Dow Jones News

By Sarah Kent

Years of painful restructuring have left big oil companies

better positioned to handle the recent decline in oil prices, but

another prolonged downturn could reinforce newfound financial

discipline that has already led to concerns about

underinvestment.

Oil giants like Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and Royal Dutch

Shell PLC have slashed costs and cut spending in recent years in an

effort to convince investors they can be resilient--and

profitable--even when oil prices are volatile.

Those efforts have paid off. The industry's biggest players are

churning out cash this year and improving returns to shareholders.

The average Brent oil price that the world's biggest western oil

companies need to break even, has fallen from more than $100 a

barrel before the price crash in 2014 to less than $50 a barrel

this year, according to Edinburgh-based consulting firm Wood

Mackenzie.

As prices have tumbled, that has left executives feeling

vindicated for remaining cautious, and well prepared for the

prospect of fresh pain ahead.

"We're very confident in the outlook for the company, not so

much in the outlook for the oil market," BP PLC chief financial

officer Brian Gilvary said.

BP has said it would be able to cover its capital budget and

shareholder payouts with cash from operations with oil at $50 a

barrel this year, and is working to bring that number down to

between $35 and $40 a barrel by 2021.

While the recent fall in oil prices is likely to reinforce the

industry's financial discipline, a harsher test could be ahead

should prices decline further. The price of international benchmark

Brent crude has plunged around 30% since its October peak, when it

reached a four-year high of more than $85 a barrel. American

benchmark West Texas Intermediate has also plummeted, falling below

$50 a barrel this week.

Big international companies generally use the Brent crude price

as a marker for strategic planning. At around $60 a barrel, it is

still at levels where the companies have shown they can comfortably

make healthy profits and it is unlikely to cause any major changes

to strategic thinking.

But if the slide continues below the $60 a barrel marker, the

broader industry could struggle to generate enough cash to fully

cover financial commitments. "$55 a barrel and below is when a lot

of companies start going cash-flow negative. Clearly if we go back

down to $30 a barrel, it's a very challenging environment," said

Wood Mackenzie's senior vice president for corporate research Tom

Ellacott.

Even if prices remain around $60 a barrel, executives face a

pressing dilemma: To maintain and grow production, they need to

keep investing in new projects, but price volatility is likely to

feed extreme caution around sanctioning large and costly

developments.

Historically, companies have ratcheted up spending in the

aftermath of an oil price decline, taking advantage of a healthier

investment environment. Not this time. Even when prices were rising

through most of 2018, big oil executives repeatedly reiterated

their mantra of disciplined spending.

"I think people--they're thinking the history is going to color

our future, and that's really not the case," Chevron Chief

Financial Officer Patricia Yarrington told analysts earlier this

month. "We have growth potential, but it's going to be at a much

lower capital rate."

Chevron is spending about half what it was in 2014 on finding

and developing new projects. Both Shell and BP have set clear

limits around their spending through the end of the decade. Exxon

stands out as an exception for laying out plans to substantially

increase capital expenditures in the coming years.

The companies say they can now do more for less and are still

growing production. On top of reigning in spending, they've

redesigned and simplified new projects and renegotiated expensive

contracts--moves they say have helped to permanently lower

costs.

Where companies have returned to drilling, they are doing it

within a strict budget. Shell, for instance, spent three years

looking at ways to make its Vito project in the Gulf of Mexico more

economic before greenlighting the development earlier this year. By

simplifying the original design and working more closely with its

contractors, the company was able to reduce costs by more than 70%

and bring the project's break-even oil price down below $35 a

barrel. Once it is up and running in 2021, Vito is expected to

produce up to 100,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day.

But some analysts and executives have raised concerns that the

industry still needs to start investing more to avoid a supply

crunch that could send prices spiking higher within the next few

years.

"Overall in the industry, the current level of investment is

probably not enough to support demand," Equinor CEO Eldar Saetre

said. "You've seen three or four years now with low investment

levels and few FIDs, and that needs to come up."

Write to Sarah Kent at sarah.kent@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 29, 2018 07:21 ET (12:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

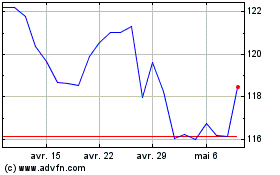

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024