King of Generics Pushes Into Biotech Drugs

13 Février 2019 - 2:54PM

Dow Jones News

By Denise Roland

The world's largest maker of generic drugs is looking for growth

in an unlikely place: high-price biotech medicines.

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., which makes more than one

in 10 drugs taken in the U.S., has been battered in recent years by

slumping generics prices, while grappling with heavy debts. That

has forced it to cut thousands of jobs and shut research

facilities. Now it is turning to biotech drugs to revive its

fortunes.

"We figured out a strategy where we'd continue to be leaders in

generics but really focus our R&D on innovative biologics and

biosimilars," new Chief Executive Kåre Schultz said in an

interview. "That's what we're working hard on right now."

Teva's full-year results Wednesday underscore the scale of the

challenge he faces. The company reported a 16% slide in revenue to

$18.9 billion for 2018, with adjusted earnings per share -- which

strips out one-time items -- down 27% at $2.92. Teva said it

expected revenue to decline further this year, forecasting sales of

$17 billion to $17.4 billion.

The lower-than-expected guidance and weak sales for one of its

newer drugs sent shares down more than 12% on the Tel Aviv Stock

Exchange.

Biotech, or biologic, drugs are made using living cells in a

process that resembles brewing. They are much more complex than

pill-form medicines and typically command higher prices because

they target specialty diseases like cancer and rheumatological

conditions.

The Israel-based company already sells some biologic drugs, but

they make up a small portion of revenue. Mr. Schultz's ambition is

for around half of the company's sales to come from biologics in

the long run.

Teva doesn't have the financial firepower to buy new drug

prospects and has had to cut its research budget. So Mr. Schultz

has halved the size of Teva's research pipeline to focus purely on

biologic drugs. It now has 25 drugs in development, mostly at an

early stage.

The 57-year-old industry veteran zeroed in on biologics after

discovering that Teva already had pockets of expertise in the area

but without focus. "The R&D strategy was really all over the

place," said Mr. Schultz, who joined Teva just over a year ago from

Denmark's Lundbeck A/S.

In doing so, he is tapping into a broader trend. Between 2006

and 2016, biologics' share of the pharmaceutical market rose from

16% to 25%, according to IQVIA, a health-care data company.

With its push into biologics, Teva is doubling down on what has

long been a lucrative sideline for the company: original, branded

drugs. For years, Teva counted on multiple sclerosis drug Copaxone

to boost profits, but sales are now dropping sharply as it faces

competition from cheaper copies.

That sideline started as a lucky break. In 1987, then-CEO Eli

Hurvitz agreed to help out a friend who was working on a new drug

at Israel's Weizmann Institute by bankrolling the clinical trials

needed to win regulatory approval. In return, Teva got the rights

to sell the drug. According to company lore, Mr. Hurvitz justified

the risky investment by carrying around a piece of paper promising

to resign if the drug failed.

Copaxone was launched 10 years later and has since generated

nearly $50 billion for Teva. At its peak in 2013, it accounted for

a fifth of Teva's sales.

Teva continued to develop innovative drugs, but its efforts

didn't yield enough to replace the revenue lost when cheaper copies

of the blockbuster emerged in late 2017.

Copaxone's decline compounded an already-dire situation for

Teva. The company was grappling with a huge debt pile and a price

war in the U.S. generic-drug market, sparked by wave of

consolidation among pharmacy chains and a sudden influx of new

competitors. Mr. Schultz's predecessor, Erez Vigodman, departed in

February 2017 and the company didn't have a permanent chief

executive for nearly nine months.

Weeks after joining the company, Mr. Schultz launched a

cost-cutting plan that involved axing a quarter of Teva's staff,

around 14,000 people, shutting around 20 of the company's roughly

80 factories and several research centers.

Mr. Schultz says the turnaround is making progress. Cost cuts

are ahead of schedule, debt has been narrowed and he expects

revenue to start edging up in 2020 as the generics business starts

to grow again. Some newer branded drugs, like migraine-prevention

treatment Ajovy and Austedo for Huntington's and other movement

disorders, could also start to gain momentum.

Despite his focus on biologics, Mr. Schultz wants Teva to remain

a dominant player in generic drugs, too. He believes the price

decline, which has halved the value of the U.S. generics market

over the past five years, is bottoming out.

And the new push may also help boost Teva in the area it is best

known for: Some of the research projects are biosimilars,

essentially generics for biologic drugs.

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 13, 2019 08:39 ET (13:39 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

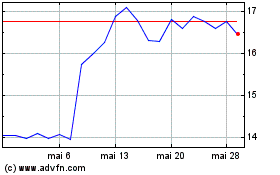

Teva Pharmaceutical Indu... (NYSE:TEVA)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juin 2024 à Juil 2024

Teva Pharmaceutical Indu... (NYSE:TEVA)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Juil 2023 à Juil 2024