Goldman Promises Greater Scrutiny of Senior Executives Following 1MDB Settlement

23 Octobre 2020 - 3:06AM

Dow Jones News

By Dylan Tokar

When Goldman Sachs Group Inc. first came under scrutiny for its

dealings with Malaysian development bank 1Malaysia Development Bhd.

or 1MDB, the investment bank was adamant: The alleged bribery

misconduct was the fault of rogue employees, according to former

chief executive Lloyd Blankfein.

By the time of its blockbuster $2.9 billion settlement with

authorities in the U.S. and elsewhere on Thursday, the bank was

singing a different tune.

Following the settlement, the bank announced an unusually broad

set of bonus clawbacks and pay cuts to current and former

executives, including Mr. Blankfein. Goldman's board released a

statement calling the matter "an institutional failure."

Central to the Justice Department's case was the repeated

failure of Goldman's compliance and internal control functions to

properly investigate the involvement of a corrupt Malaysian

financier who was involved in the 1MDB bond offerings underwritten

by the bank.

Mr. Blankfein and others at Goldman for years blamed the scandal

on a pair of senior bankers who were criminally charged in the

matter, Timothy Leissner and Roger Ng. The two circumvented the

firm's internal controls to work with financier Jho Low to secure

business from 1MDB, the bank said.

Yet fault for the misconduct, and the continued dealings with

Mr. Low, extended beyond Messrs. Leissner and Ng, according to

Goldman's agreement with the Justice Department.

The bank's control functions vetted Mr. Low in 2009 and refused

to onboard him as a client. Mr. Leissner kept trying, prosecutors

said. He and others later worked with Mr. Low to underwrite three

separate bond offerings for 1MDB worth more than $6.5 billion.

Although the bank's control functions suspected Mr. Low's

participation in the bond offerings, they repeatedly failed to do

anything other than ask members of the deal team whether he was

involved, prosecutors said.

Mr. Leissner denied Mr. Low's involvement and the oversight

functions accepted his denial, doing little else to investigate the

matter, they said. Prosecutors specifically faulted the control

functions with failing to review the electronic communication of

deal team members for concrete evidence of Mr. Low's

involvement.

The settlement documents portray a business environment where

compliance officers and other institutional checks had little power

to override high-profile bankers or lucrative investment deals.

In one email cited by prosecutors, executives in the bank's

control functions discussed the disparity between how certain deals

were vetted and the unusual latitude given to certain employees

such as Mr. Leissner.

"Yes, double standard, and it looks stupid," one unnamed

executive said.

Goldman on Thursday reached coordinated settlements with the

Justice Department, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission,

the Federal Reserve and the New York State Department of Financial

Services, and with foreign authorities in the U.K., Hong Kong and

Singapore. In July, it agreed to pay $2.5 billion to the government

of Malaysia.

As part of the settlements, the firm agreed to continue

overhauling its compliance and oversight functions. Goldman on

Thursday released a seven-page statement outlining completed and

ongoing enhancements.

Since the 1MDB transactions eight years ago, its compliance

department has nearly doubled in size, Goldman Chief Executive

David Solomon said.

Many of the enhancements outlined are standard best practices

for a firm such as Goldman, according to Bruce Searby, a former

federal prosecutor. Mr. Searby said the reforms appeared to give

the compliance functions and others within the firm greater power

to vet risky deals.

"What they are faulting Goldman for is not having enough

barriers to the deal team pushing back on the compliance team," he

said. "At least under some circumstances, you cannot simply accept

the denials of your own people."

Among the changes made or proposed by the investment bank is an

increased scrutiny on senior employees who are involved in

high-risk areas of business. The bank says it has developed a

program to conduct in-depth reviews of senior employees and

reviewed its process for approving their travel and entertainment

expenses.

The changes force executives to take on a more personal role in

oversight, said Michael Weinstein, a partner at Cole Schotz PC who

serves as chair of the firm's white collar litigation and

government investigations practice.

"The people that were handling deals in [the 1MDB case] seemed

to be at such a high level that no one questioned what they were

doing," he said. "They are saying, 'We can't let that happen

anymore.'"

Write to Dylan Tokar at dylan.tokar@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 22, 2020 20:51 ET (00:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

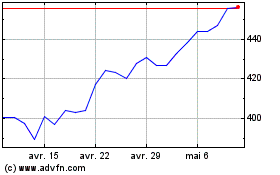

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Mar 2024 à Avr 2024

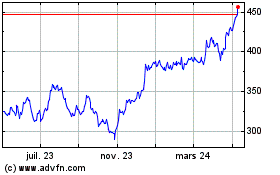

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Graphique Historique de l'Action

De Avr 2023 à Avr 2024